“Miss Desjardin came running over to her, and she wasn’t laughing anymore. She was holding out her arms to her. But then she veered off and hit the wall beside the stage. It was the strangest thing. She didn’t stumble or anything. It was as if someone had pushed her, but there was no one there.”

From We Survived the Black Prom, by Norma Watson.

Source: Bought copy

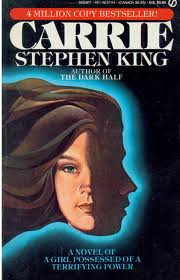

Publisher: Penguin

Publication Date: April 5, 1974

Carrie White is a misfit—always has been as a matter of fact. A scapegoat for the other teens at Thomas Ewen Consolidated High School, she’s the one you mock when you want to make yourself feel better. She’s a bully’s dream—awkward of both speech and manner—the perfect patsy. Her mother has spent Carrie’s 16 years on this earth tormenting her, punishing Carrie for her own supposed iniquities. Years of suffering the taunts of her schoolmates and her mother’s insanely religious fervor have turned Carrie from a pretty little blonde haired child into a mousy and introverted teen, too cowed to put up a fight when faced with the pettiness and enmity of her social peers. There’s no fight in her and they know it.

After Carrie suffers a particularly brutal taunting session in the girl’s locker room, Sue Snell, a girl with a modicum of shame for her participation, devises a plan to atone for her behavior, and maybe rehabilitate Carrie’s image. She wants to do something nice for the girl she pities and in the process absolve herself of her guilt. Sue’s boyfriend Tommy Ross is one of the popular kids. He’s also a genuinely kind soul and in love with Sue, so when she suggests he ask Carrie to the prom in her place, he says yes. Not because he pities Carrie, but because he loves Sue. Neither of them could predict the consequences of their good deed, neither for themselves, nor Carrie, nor the good people of Chamberlain Maine. You see, Carrie has a secret, and one last humiliation will be all it takes to put her over the edge and unleash a fury that will make everyone at the prom of ’79 regret ever taunting her—if they survive.

In a day and age where the problem of bullying has become prevalent (or at least more noticeable do to the rise of social media), Carrie has a timeless feel. It’s eminently relatable to anyone who’s gone through the experience of high school and the various injustices we all committed or been subjected to. Part of the thrill of Carrie is the satisfaction involved in watching her unleash the terror of her power on those who’ve tormented her all those years. Who hasn’t dreamed of getting revenge on those who’ve bullied us in the past? It’s juvenile, but then this is the story of juveniles.

But King doesn’t bludgeon us with stereotypes. It’s not a case of Carrie versus a bunch of shitty, one dimensional teenagers. There are moments at the prom where we get to see glimpses of Carrie’s schoolmates, and they’re not caricatures—there’s no black and white. When Tommy Ross introduces Carrie to George Dawson and Frieda Jason, he shows us that Carrie’s later fury is misplaced, and that is one of the more horrifying aspects of the novel’s climax. Most of those Carrie hurts don’t deserve it.

Tommy Ross is the most relatable and adult character of the novel. He’s no fool; he knows high school is not the real world and what teenagers find important is not a reflected in reality. It doesn’t matter if you’re the captain of the football team or the misfit sitting in the corner of the library trying not to be noticed. High school is a transitory phase of life, and unlike a lot of teens, he knows it’s not the end all and be all in life. As for Sue Snell—her motives are less clear. She comes across sympathetically, sincere in her efforts to atone for abusing Carrie but tarnished by the possibility that she’s atoning for her own selfish purposes. Chris Hargensen’s motives are clear and simple—hurt Carrie—whom she sees as the author of her misfortunes. She’s a spoiled girl who’s never had consequences for her actions, and isn’t prepared in any way for what results from her prank at that ill-fated prom.

The one character who’s definitely a stereotypical horror trope is Carrie’s mother, Margaret White. The religious freak (for lack of a better term) has been a favourite of horror authors for at least as long as I’ve been a reader, and I find it a worn and lazy trope. Christians are an easy target, generally unfairly portrayed in literature as either religious zealots or rigid and unfeeling automatons. It’s tiresome and disingenuous. However, King wrote this novel back in 1974 and therefore I suspect two things: that the trope was perhaps not a trope back then and that he’s partially responsible for creating a trope that would permeate through the genre of horror fiction. I will admit that he did a wonderful job. Margaret White is the iconic example of the type—a batshit crazy zealot, blending her religious zeal with a serious mental illness. Her constant bullying of her daughter—for simply existing—gives the reader some large gratification when she finally meets her fate.

Now Carrie is a much different story.

Even knowing the horrible revenge she exacts on her schoolmates, it’s impossible not to have sympathy for Carrie White. She’s such a beaten down character, but not in any way a horrible person. She has the same dreams as her peers; she yearns for the acceptance every teen wants. She’s got the same schoolgirl crushes (Tommy Ross) as all the other girls, but just doesn’t quite fit into any of their cliques. Undeserving of the hideous prank Christine Hargensen and her psychopathic boyfriend Billy Nolan play at the height of the prom, it’s with a certain amount of perverse satisfaction that we as readers observe the reign of terror she presides over in the latter half of the novel.

The theme of redemption and revenge weave through the core of this novel. Redemption is the defining desire of many of the characters. Carrie wants to redeem her life—be a normal teenager—before it’s too late. Sue Snell wants to redeem her good character, hating to be seen as just another bully, even if it’s in her own mind. Even Margaret White is looking for redemption in her own twisted way, culminating in her attempt to kill her own daughter in “repentance” for her sins. As for revenge, it’s what motivates everything Christine Hargensen does. Christine sees Carrie as the manufacturer of her misfortunes, blindly ignoring her own culpability and literally lusting at the idea of putting Carrie in her place. Billy Nolan goes along with her plan for much the same reason. And then there’s Carrie. She seeks revenge for her humiliation, for what happened to Tommy, for 16 years of constant torture at the hands of pretty much everyone.

In Carrie, Stephen King wrote a novel that is both chilling and heart wrenching, creating in Carrie White a character that is both villain and victim, and enticing the reader to care about a young girl essentially turned mass murderer. Carrie may be one of Stephen King’s earliest novels but to me it still ranks among his best. It’s also one of his shorter works, and you will most likely find yourself burning through the story in one, maybe two reading sessions.

Carrie was published April 5th, 1974, forty years ago today, and in honour of the anniversary Matt Craig over at Reader Dad conceived the wonderful idea of a series of tributes and the simultaneous publishing of various bloggers reviews of this seminal work in the genre of horror fiction. It’s been an honour taking part.

I love King but i hate this book

LikeLike

It’s funny that you should say that. I’m not a big fan of his later works. Did not enjoy Cell at all, nor The Regulators, really anything since he finished the Dark Tower series. However, I love most of his earlier works.

LikeLike