A man in a robot suit walking down the road, a sign above his head: Half price tickets. ‘There’s no place like home!’ the man shouted. He stopped by Joe, handed him a leaflet. ‘There’s no place like home, mate. Get a ticket while they’re going.’

Joe blinked, his vision blurred. The tin-man walked away. He’d already forgotten Joe. ‘No place-‘

‘Joe?’

He blinked and opened his eyes. Madam Seng stood above him.

‘You’ve had a bad dream,’ she said.

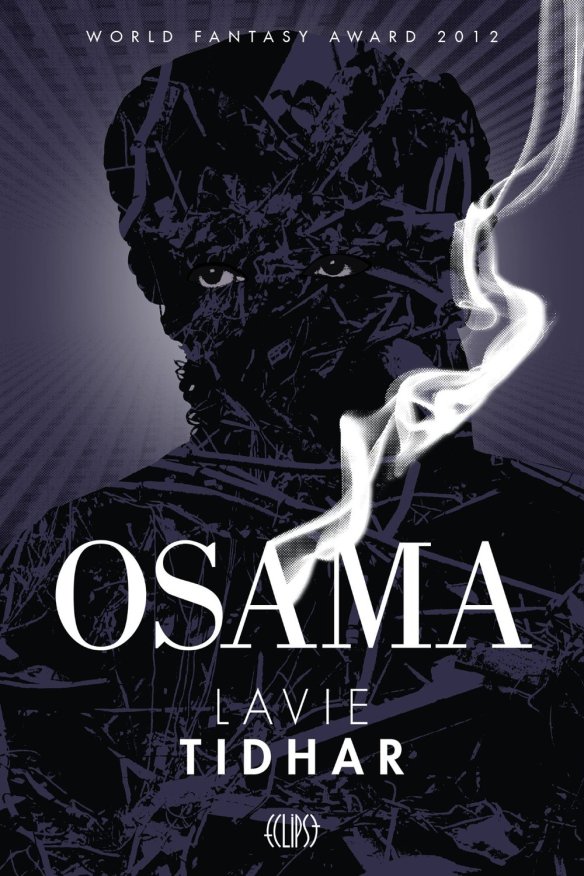

Source: Bought copy

Publisher: Solaris

Date of Publication: October 9, 2012

Joe is a detective, average and nondescript. Living in Vientiane, Laos, he spends his mornings drinking coffee in a local café and afternoons reading in his disheveled office, quietly shared by him, a desk, and a gaggle of geckos. He sits and he reads and he smokes, whiling the time away.

And then the girl appears, the girl in need of a detective. She wants to find a man, an author, coincidently, the author of the pulp thriller sitting on Joe’s desk. The man, who writes about a fictional terrorist, a terrorist whose exploits titillate the reader with his exceptional violence. She wants him to find the unlikely named Mike Longshott, author of the Osama Bin Laden—Vigilante series, and money is no object. Then she disappears as if she were never there.

Joe—doing what a detective does—takes the case, commencing a journey that will take him across the world and back, from the banlieues of Paris to the heart of London and then New York, finally across Asia to Afghanistan and a Kabul that has always been and never was. Harassed and impeded at every turn by a mysterious group determined to keep Longshott’s anonymity intact, Joe’s pursuit of the pulp author slowly transforms into something altogether different, a search for a truth that once discovered, will slowly unravel his understanding of both reality and his place in it.

Reading a novel by Lavie Tidhar can be a lot like trying to wrestle with smoke. Reality is reality, until it’s not, as if it simply blew away in the wind. And that’s why if forced to describe Osama in a word, that word would be “surreall”. Tidhar’s novel starts innocently enough, at first appearances a traditional boilerplate mystery. Mysterious woman hires “down on his luck” detective to find equally mysterious writer. Woman looks familiar, but detective can’t quite place where he’s seen her before. Detective is given an expense account, begins his search and almost immediately finds himself the target of a nefarious cabal determined to stop him—all very much Mystery 101.

Or is it?

It quickly becomes obvious that Osama is not your traditional mystery, and as time goes on, Joe’s journey devolves into a schizophrenic dream —a locked room mystery where the room is Joe’s reality, and the mystery is the truth of his existence. You see, reality is malleable in this Tidhar novel, dependant more on the reader’s point of view than any natural laws.

For instance, the world Joe inhabits is one where Osama Bin Laden is merely a character in a novel. Al Qaeda, 9-11, the invasion of Iraq and subsequent global jihad—they never happened. The World Trade Centre is but an architect’s dream, and the world is relatively peaceful. Yet many people in Joe’s world have glimpsed another, a world where Longshott’s Bin Laden thrillers aren’t merely figments of a frenzied imagination. As the case deepens, Joe begins to realize he is one of these select few, drawn to this other world like a moth to flame. The reader is drawn to Joe in much the same way, as one realizes the mystery of Osama has more to do with Joe and Osama than it does the man Joe is trying to track down. Osama the fictional character is linked to Joe the real detective—but how?

We’re given clues to their connection as Joe comes into contact with others who share this ephemeral bond, refugees, as they’re called. Who or what are the refugees? Spectres? Transients from another reality? Figments of Joe’s imagination? There’s a host of possibilities, left up to the reader to decide. Perhaps Joe and the other refugees are those whose deaths in our world transported them there by the inhumanity of what happened to them. Perhaps Joe’s reality is merely a construct of a man on his death-bed, unconsciously trying to make sense of what happened to him. Perhaps it could even be that Joe’s world is purgatory for those who died so quickly they aren’t even aware of their own passage. It could also be the story of an alternate universe whose borders on our reality are ill-defined.

Just like the setting, the characters inhabiting the world of Osama are as fleeting as their reality. Osama is a McGuffin of sorts, merely sliding between the pages—the object of Joe’s fascination while he searches for Mike Longshott, much as the Maltese Falcon drove Sam Spade while he looked for Archer’s murderer. Mike is the link binding the story of Joe with that of Osama. He’s the facilitator, unintentionally leading Joe to discover the truth of his own existence, and by extension, that of the girl. He doesn’t recognize her, but she’s clearly familiar with him, as if there were a time and a place where they once knew each other.

And that’s the thing about Tidhar’s characters. They’re all as ephemeral as the situations in which they’re placed. There’s a sense of unrealness, an unfinished quality about them. Joe is the only character of substance, and even that becomes questionable as the novel progresses and both he and the reader begin to question his reality.

The obvious comparison can be made between the works of Philip K Dick and Lavie Tidhar. At first I thought that might be unfair, as Tidhar has his own voice and style, but after reading Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, the similarities in their writing come to the fore. Tidhar plays with much the same themes regarding reality and one’s perspective, and has clearly been influenced by Dick’s writing. For instance, there’s a scene in Osama where Joe enters an opium den to confront the proprietor, using the delivery of a film case as part of his ruse. He quickly falls into a fugue state while the film is shown and finds himself in another London, one that looks much the same, but with subtle differences. The film acts as a catalyst for his transference between worlds, much as the talisman Mr. Tagomi is meditating with in MITHC when he finds himself transported to an alternate Los Angeles where America won the Second World War. In another scene, Joe is trying to gain entrance to a private club known as “The Castle”, another less than subtle reference. While each author clearly has their own voice, Tidhar has clearly produced an homage to a master of the alternate history genre using his own distinctive style.

Osama is not a traditional novel, in that the process is more important than the final product. There’s no clear resolution to this mystery, and it’s almost as if it’s a very well written thought experiment. A multitude of solutions are posed, but you’re going to have to settle for whichever one you WANT to be the solution. In the end, that’s what makes Osama a most satisfying read.